(Program)

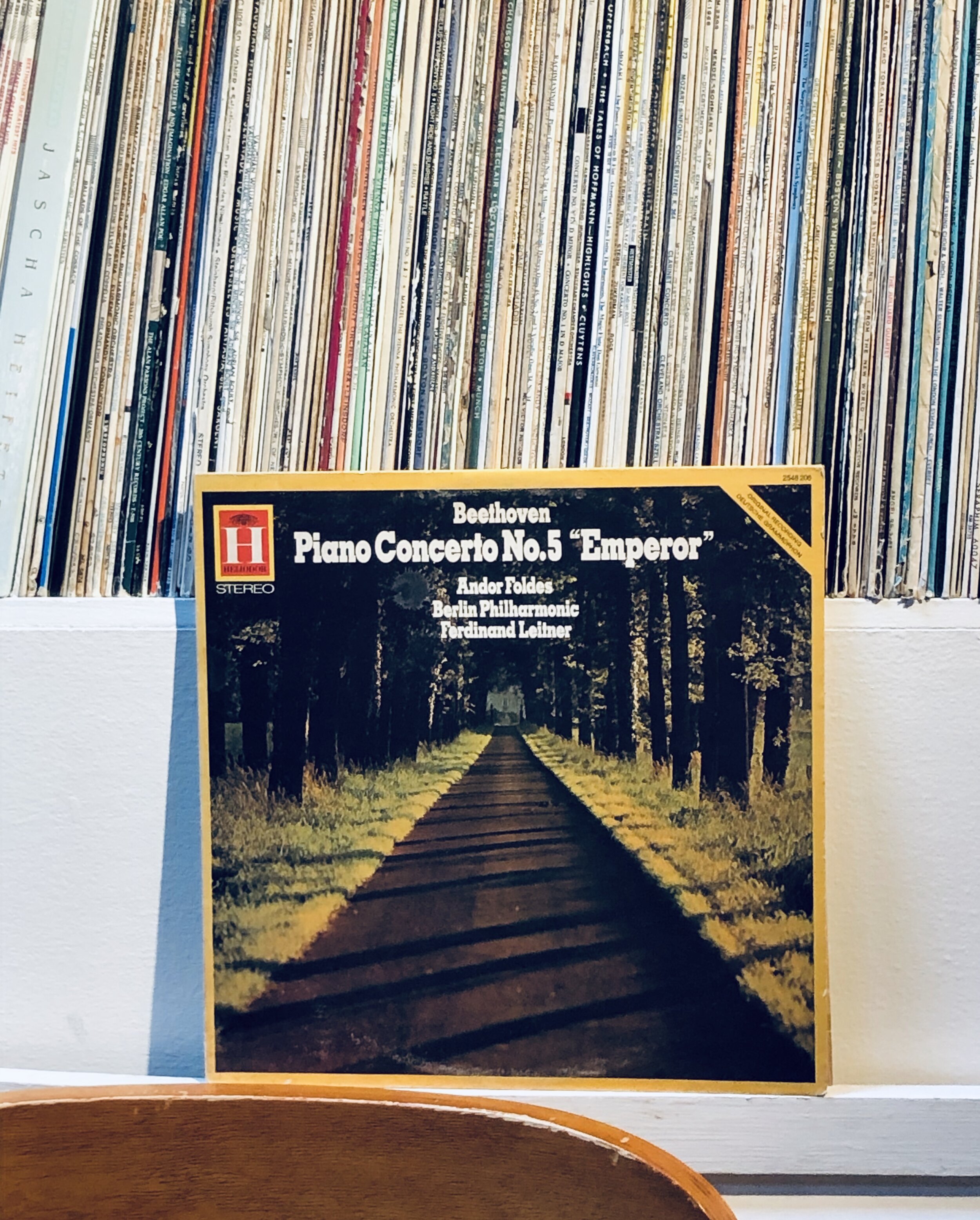

Deutsche Grammophon Original Recording // Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827) // Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No.5 in E flat major,

Berlin Philharmonic, conducted by Ferdinand Leitner. Pianist: Andor Foldes.

Piano Concerto No.5

1. Allegro

2. Adagio un poco mosso, attacca

3. Rondo: Allegro

What have you got to say, my friends

About this painful time we’re living through?

You’ve left this desert where you say you were born,

You’ve gone and abandoned it

We live in ignorance and it holds all the power…

“” Imidiwan ma tenam — Tinariwen

the plot thickens. two weeks into quarantine and i’m running out of outfits to wear to the living room.

dire times call for dire measures, the impulse is to scale down expenditures of energy to only the most ‘essential’ needs; beethoven can wait, so too can the rest of our artistic needs.

nevertheless, it is in times of inconvenience and unaccountable interruptions to the usual order of things that we most stand in need of art’s extravagances. to focus our attention on hope—yes, but also to apply periodic dosages of an essential type of pressure: to fasten our expenditures with the strictures of an aesthetic discipline.

whether its the $50 left in the bank account, or the proceeds that flow freely from being very gainfully employed (as was the case in the bygone age of early march), what we expect and demand of beauty remains the same.–—that is the elaboration of the abbreviated reaction i throw at every instance of panic in regards to the current situation: beethoven can’t wait. especially now, great music is needed, because great music contains in it a timelessness.

or at least its own sense of time, as a corollary or perhaps an alternative to the actual passage of time.

earlier this week i finally ridded myself of an essay, two months in the making, for a course on the western musical tradition. my topic of choice was a the history of racism in classical music; in particular, the plight of william grant still, the composer behind the Afro-American Symphony, and alleged ‘dean of Afro-American composers’. it’s a meandering attempt to argue against classical music as a specifically european aesthetic, against the hyphenated identities that are seemingly benign, but perpetuate the otherness of visible minorities and women participating in the genre (‘black-composer’ ‘female-composer’ etc). it somehow ended in the unexpected conclusion that placed just as much blame on the insistence on race as an aesthetic, an angle suggested by what the composer’s wife had to say in response to those—mostly other black people—who insisted that ‘racial idioms’ like those found in the Afro-American Symphony are incompatible with the ‘white world’ of classical music’s aesthetic.

This black, black, black thing is going to be a dead-end street eventually…My brother was teaching in the University of Mississippi…in the scientific field, and I said, “Have you had any difficulty with militants?”and he said, “No, we haven’t yet been asked to teach black biology.”…If you get to the ultimate in this black business, that means that nobody but Black people can play a black composer’s music, and nobody but Black people can listen to it. This is ridiculous. “” verna arvey still, unplished interview: february 24, 1973

that got me thinking, about the aesthetic communicated by the industry of musicians, programmers and recordings perpetually pumping out beethoven’s total output. if it’s a specifically european aesthetic, then the degree to which participants, such as myself, can make something personal of the music is constrained by the low-resolution of race-relations. but if it’s the case—as the month of beethoven on here has been trying to root out—that the composer’s penchant for individuation (in the jungian sense) liberates him from his nationality towards something more universal (thereby making him a very good european, according to nietzsche) then would he be perhaps more communicable to a ‘black’ guy in toronto in 2020? yes is the respond you’d be inclined to give if you believed in the beethoven that’s been marketed in the last century: a composer beyond the european aesthetic (though i can’t imagine a more european word than beethoven), whose stylistic identity, in the sense described below, is too unique to be anything but individual:

‘Beethoven’ by Jeremy Lewis @jplewisandsons for blue riband

The slow movements are as impressive as the fast and furious, the serene episodes at least as memorable as the violent. For every shock there are a hundred exquisitely turned phrases and a hundred delicate combinations of tone colours, using just the same instruments as Haydn and Mozart, but sounding like nobody but Beethoven. Because of this enormous range, for many listeners Beethoven is the composer who seems to convey in his music the greatest understanding of human life, in all its complexity. […] One the other hand, in recent decades there has been a counter-movement to strip away all the baggage of tradition, to abandon the Romantic myth of Beethoven the Great, and to try to recreate his music as it might have sounded when it was fresh in his lifetime. “” robert philip, The Classical Music Lover’s Guide

no—if you believe, along with the aforementioned ‘militants’, that his is irredeemably the music of the ‘white man’s world’, and doubt if his understanding of the complexities of human life included that of ‘black’ life. as if race was itself an aesthetic that classical music could not understand and therefor can not reach, as if there was “some sort of “blackness” that White people can’t understand, and some sort of “whiteness” that Black people can’t fathom.”

The militants justify the exclusion of the most distinguished Negro doers and thinkers by their allegiance to “Black Pride.” It is asserted that Black people should be proud of aspects of their culture that are peculiarly their own, and that they should shun those things that are part of the White man’s world. Black pride means a disdain for anything belonging to “Whitey” — even traditional schooling, standard English, and classical music—and an inclination toward the total separation of the races.” “” judith anne still: William Grant Still: A Voice High-Sounding

anyways, that’s where my mind has been this week; perhaps in the next one i’ll have more to say on the particular work. though i was especially looking forward to this Emperor concerto when i purchased it back in august, in anticipation of jan lisiecki and the TSO’s performance that would have otherwise happened next wednesday. the work is more typical of the composer than the more introverted Piano Concerto No.4; it’s intimations of spring are only surpassed in vivacity by the Pastoral Symphony, (which i’ll be listening to next week). an interview with lisiecki in regards to the Emperor is currently in the works, as a commentary on the work, the composer and the concert that would have been.

(song of the week: Imidiwan ma tenam — Tinariwen (ft. Nels Cline of Wilco))

and now for something completely different: discovering Tinariwen has been a brilliant accident in music—there’s nothing else in my music library quite like the aerobic fitness of the rhythms that animate the crackling energy of their tamasheq (the language of the tuareg people).

bands like Tinariwen and Tartit walked decades ago so that my beloved Bombino could run.

this is the music that feels instinctive to me, it’s how music sounded to me growing up in nigeria. as such there was something instinctively foreign to me at first exposure to classical music, the same sensation that world music perhaps invokes on someone raised on a classical music diet.

Tinariwen also makes for a great running playlist, if you’re one of the those who’ve suddenly started training for a marathon as a result of the quarantine.

What have you got to say, my friends

About this painful time we’re living through?

You’ve left this desert where you say you were born,

You’ve gone and abandoned it

We live in ignorance and it holds all the power

The desert is jealous and its men are strong

While it’s drying up, green lands exist elsewhere

We live in ignorance. And it holds all the power

Imidiwan ma tennam dagh awa dagh enha semmen

Tenere den tas-tennam enta dagh wam toyyam teglam

(Imidiwan ma tennam dagh awa dagh enha semmen

Tenere den tas-tennam enta dagh wam toyyam teglam)

Aqqalanagh aljihalat tamattem dagh illa assahat

Tenere den tossamat lat medden eha sahat

(Imidiwan ma tennam dagh awa dagh enha semmen

Tenere den tas-tennam enta dagh wam toyyam teglam)