Think of a man whose health can never be restored, and who from sheer despair makes matters worse instead of better. Think, I, say, of a man whose brightest hopes have come to nothing, to whom love and friendship are but torture, and whose enthusiasm for the beautiful is fast vanishing; and ask yourself if such a man is not truly unhappy . . . . “” franz schubert to leopold kupelweiser, march 31st 1824

in contrast to this type: just last week with saint-saens who was praised by musicologist watson lyle for not belonging to “that pathetic band of pioneers in the history of the arts and sciences, whose mortal span fell short of the length of their spiritual mission….” except there is nothing pathetic about this pioneering sort, and with very few exceptions the ability to maintain so long a creative lifespan like saint-saens’ owes as much to the curtailing of the pursuit of spiritual missions as to being born into enough of a socioeconomic standing to avoid resorting to spirituality. (yes, every kind of spirituality is always a last resort, the only backseat available when vitality and virility and other kinds animal vigor, are depleted…)

Schubert never came near the imperial court, even though Antonio Salieri, the imperial director of music and Schubert’s teacher in composition, had the highest opinion of his talent. Why did Salieri not introduce him, as Mozart was introduced, at the Vienna court? We know the answers: Emperor Franz II was not interested in music, and on the other hand Mozart’s father was a first class impresario. “” egon f. kenton, notes from the recording

some perhaps suffer too much and too early from that kind of depletion. and fewer still are able to transmogrify this decline into a creative surplus. franz schubert—of which every surviving sketch depicts him as a man mushrooming out of his own little sartorial outpost—is that other kind of genius i briefly referred to last week in contrast to the more prevalent (though often less consequential) kind that lives for eighty years on a steady diet of popular aesthetic sentiments that can fill a room—perfectly round, perfectly rotund and perfectly indispensable…

Schubert stayed in Vienna, composed and hoped. His hopes were realized only in small measure — a few works performed, a few published. Then came illness, and death on November 20, 1828, at the age of 31. “” egon f. kenton, notes from the recording

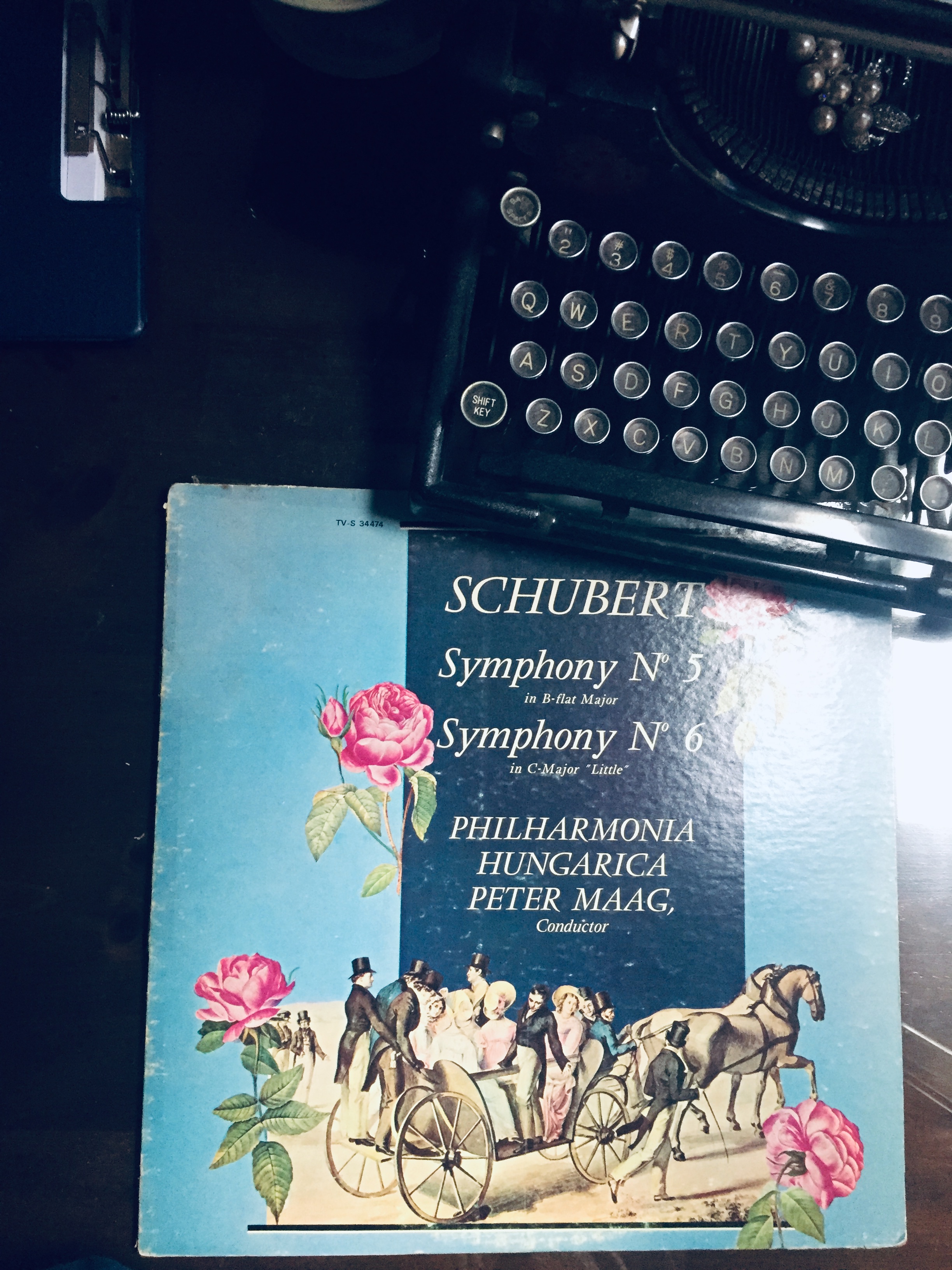

aside from a predisposition to sickliness, what schubert also suffered from—of which his art eventually survived, posthumously—is perpetually finding himself in the periphery of social action… the cover art for this recording is a procession of well to do top-hatted socialites trotting along in a wagon-buddy hybrid drawn by two impossibly athletic horses. in the very background and to the left, as an afterthought, is an almost imperceptible image of a figure resembling schubert: gesticulating awkwardly in conversation, his neck and face shrooming out his collar.

Schubert never had any encouragement to write symphonies, as not one of them was ever performed by a professional orchestra during his lifetime. The only incentives he had came from the small amateur ensembles in his lower-middle-class suburb, and from his own inner urge. It is a wonder that he nevertheless composed two such masterpieces as the Unfinished and the great C major Symphony. “” egon f. kenton, notes from the recording

nevertheless; nevertheless, he wrote music—these two symphonies especially—as if he was up there, front and centre in that horse drawn buggy. the kind of music that reminds one that the classical repertoire is a result not of a burning kneeling deep-needing to express some urgent, insurgent ideation—but the necessary conclusion that music is needed, needed in tremendous and sustainable quantities and that a composer is a above all else a manufacturer of and to this need. it is miracle that people who have so little of their own, who have been weaned on so little, nevertheless are able to maintain a posture in their artistic output that suggests they have grown accustomed to not only living, but also of the excesses of life. on this topic do i recall what i once read in the diary of some gaunt french priest: ‘Oh the miracles of our empty hands!’...

(program)———

Turnabout Vox. Printed in the USA // Franz Schubert (January 1797- November 1828) // Symphony No.5 in B-Flat Major D.485; Symphony No.6 in C Major D. 589 “Little” //

Philharmonia Hungarica Conducted by Peter Maag

Symphony No.5

1) Allegro

2) Andante

3) Menuetto - Allegro molto

4) Allegro Vivace

Symphony No.6

1) Adagio; Allegro

2) Andante

3) Scherzo - Presto; Piu Lento

4) Allegro Moderato

It is of course not the aristocracy, the nobility, or royalty that matters but their culture, their cultivated taste, education and knowledge, their experience and ability to discriminate, and last but not least their means — the means to reward an artist and make the execution or performance of their works possible. Up to the mid 19th century, roughly, all this was the privilege of aristocracy, both clerical and secular. “” egon f. kenton, notes from the recording

(his impromptus)———even amidst the stateliness and grandeur of these two symphonies, there are occasional bouts of that insurgent restlessness. especially so in the sixth symphony wherein the flutes seem to draw you into a barely audible intimacy only for the alarming ignitions of the string section to upheave you with their sudden explosions. example of this is the last five minutes of the fourth movement of the fifth symphony—the absolutely gorgeous allegro vivace that seemingly can’t make up its mind whether it wants to be subtle and stately or urgent and impassioned--and becomes hesitating mix of both:

my favourite experiences of schubert however are on the solo piano, or piano accompanied by cello. his four impromptus (op.90) are about the most scenic and densely packed piano compositions i’ve ever heard. the fourth of those impromptus is an exhilarating and exhausting caterwaul of notes, exactly the kind of music characteristic of a composer constantly ‘venting his spleen’. there is a mesmerizing and shimmering effect generated by the upheaving rivulets that unspool from the hands of the pianist capable to taking the challenge. a seemingly possessed performance by evgeny kissin is the best recording i could find, though he plays it a tad bit too fast:

30.01.2018. Ohh mah gaawd, he on x-games mode...!

but my absolute favourite piece by schubert is his Ständchen. it’s the kind of music that feels as if borne of a singular mood, in a language of its own, one that you’re fluent in from the very first time you hear it. i have not since found a comparable composition for the cello and piano. not that it needs one, but as a companion piece, sylvia plath’s poem ‘The Two Sisters of Persephone’ reads almost as if it was written for this performance by the beatrice berrut and the magnificent camille thomas:

Two girls there are : within the house

One sits; the other, without.

Daylong a duet of shade and light

Plays between these./

In her dark wainscoted room

The first works problems on

A mathematical machine.

Dry ticks mark time/

[...]

Bronzed as earth, the second lies,

Hearing ticks blown gold

Like pollen on bright air. Lulled

Near a bed of poppies,/

[...].

On that green alter/

Freely become sun's bride, the latter

Grows quick with seed.

Grass-couched in her labor's pride,

She bears a king. Turned bitter/

And sallow as any lemon,

The other, wry virgin to the last,

Goes graveward with flesh laid waste,

Worm-husbanded, yet no woman."" Sylvia Plath, The Two Sisters of Persephone